Introduction to Audio Storage

Sound

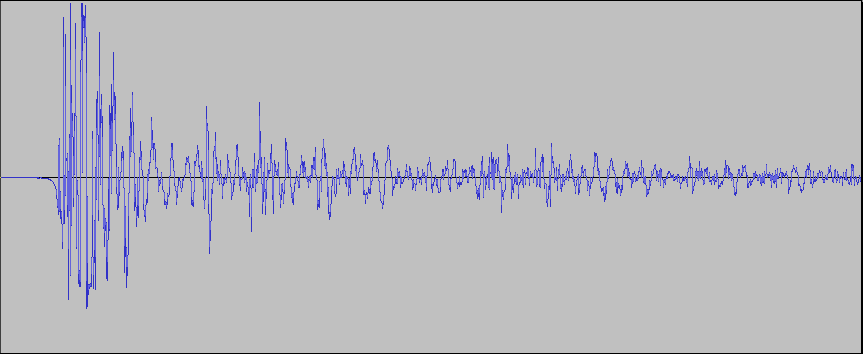

Sound moving through the air is composed of small changes in air

pressure that move rapidly (at the speed of sound, 1,230 km/h at sea

level) out from the source. In our ears there is a small membrane

and a set of bones that is capable of sensing these tiny (and very rapid)

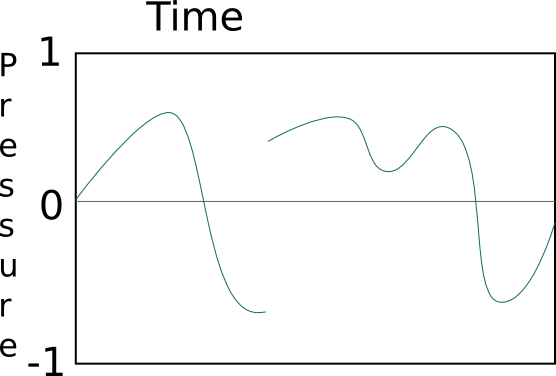

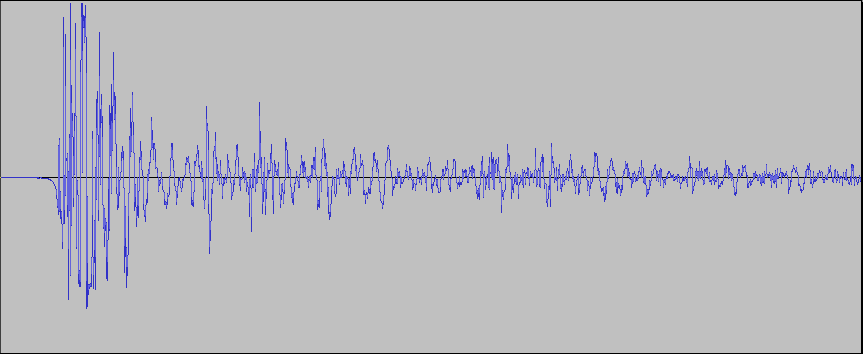

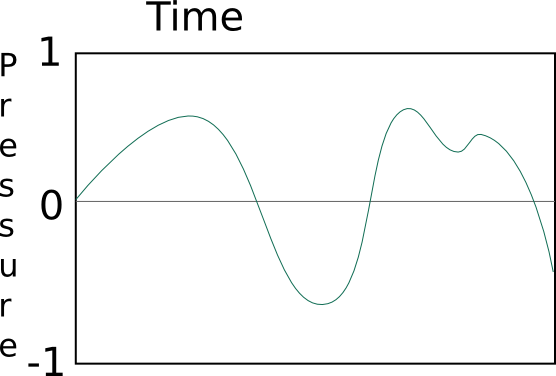

changes in pressure. Here is a graph of what the pressure

recorded near by a set of hands clapping one time looks like. This sample was

recorded by a microphone over 5/100ths of a second or 0.05

seconds. To listen to the

audio file, save it to your computer and

open in VLC or Audacity:

As you can see in the above graph (called a "waveform"), a sound that

we think of as one instantaneous event, is

actually composed of several different changes in pressure.

Spikes above the middle of the graph indicate higher pressure and

below the graph indicate lower pressure. Areas where the curve

goes further away from the center of the graph (both higher and lower)

are loud. Areas where the curve stays close to the center are

quiet. In this graph the loudest part of the clap is at the

beginning, then it trails off over time (remember the entire graph

above is only 5/100ths of a second).

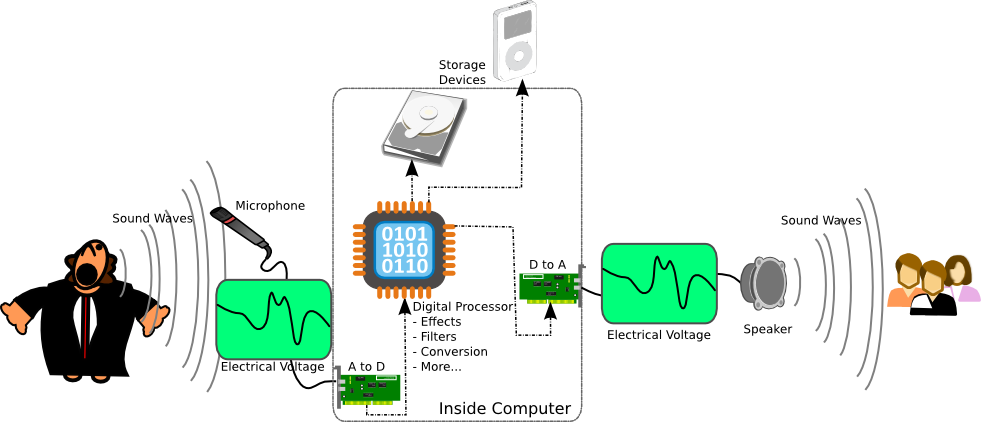

We used a microphone

to record these changes in pressure. A microphone has a component

that is susceptible to tiny differences in pressure (like a very small

balloon) and couples that with a component that can change the amount

of electrical voltage moving through a circuit. There are many

different methods for doing this, but the end result is that all

microphones convert the changes in pressure that pass over them into

changes in electrical voltage that can be sent down a wire into a

recording device, in this case a computer.

Sound generally

doesn't move any air, it simply compresses/decompresses it to

higher/lower pressure for a split second at a time. Because of this, the pressure

changes above and below the curve must balance out. Each time the

pressure goes through all the phases: go up above the curve, come back

down to the curve, continue down below the curve, and finally come back

up to

the curve; making one complete loop, this is called a cycle. The

number of cycles per second

that the sound does this is is called the rate or frequency, the unit for which is

Hertz, abbreviated Hz. So if a particular sound is at 500 cycles

per second, we call that 500Hz. We can also use the standard

metric prefixes for it. A sound at 31,000 Hz could be written as

31kHz. Just for a reference, the human ear can detect sounds from

approximately 20Hz up to 20kHz.

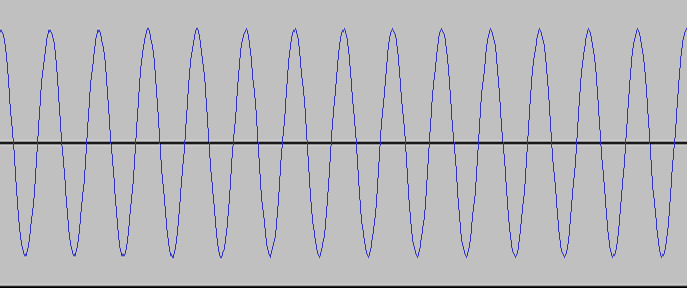

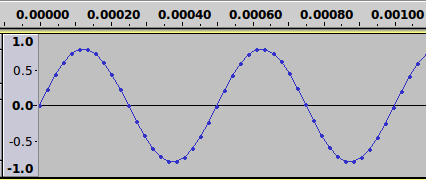

The way we hear the frequency is as different tones. It is

possible that we will have a tone with only a single frequency.

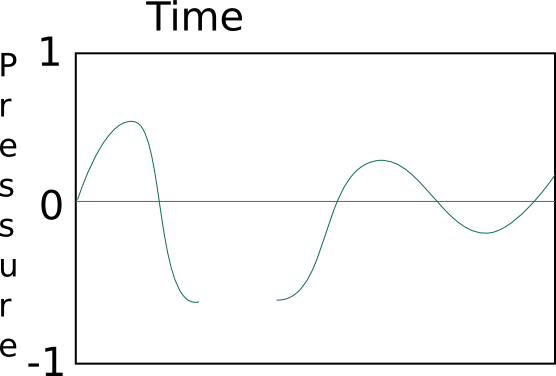

An example of that is below with a 2kHz frequency and the length of the

graph is only 0.01 seconds long:

As you can see, it takes exactly 1/2000th of a second for the wave to

go from the center up, all the way down, and back to the center.

Here is a longer example of the same

sound to listen to (save it and open it in VLC or Audacity). You

can see that this pure tone sample is a lot different than the clap

example above. This is because, most sounds that we hear aren't

exactly one frequency, but rather a mixed-up jumble of frequencies that

we hear all together. What happens is we'll hear thousands of

different frequencies each second, each for a very short amount of

time. The way this happens, it that the waves of the frequencies

will either work together to make that particular part stronger, or go

against each other to make a part weaker.

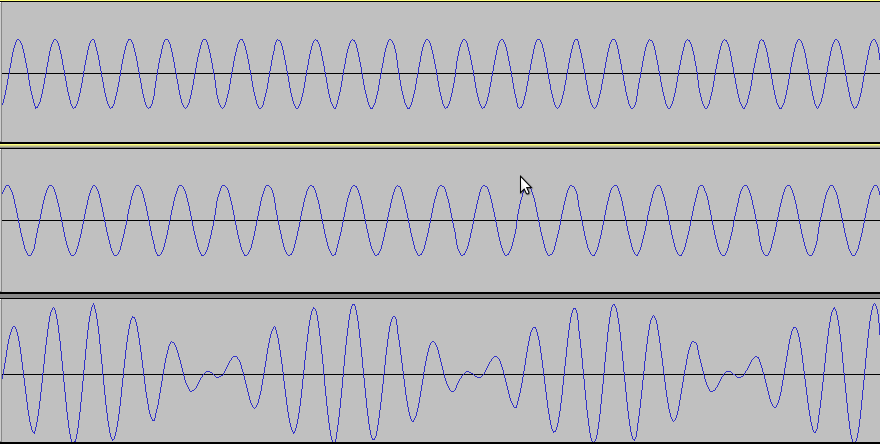

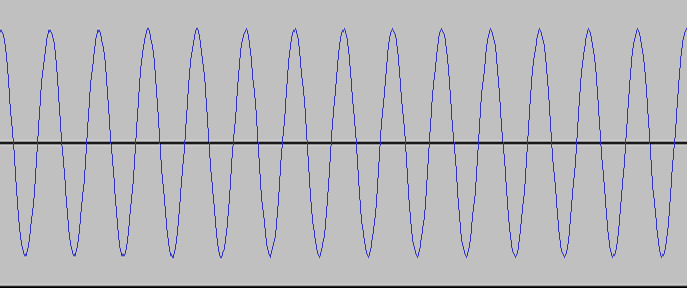

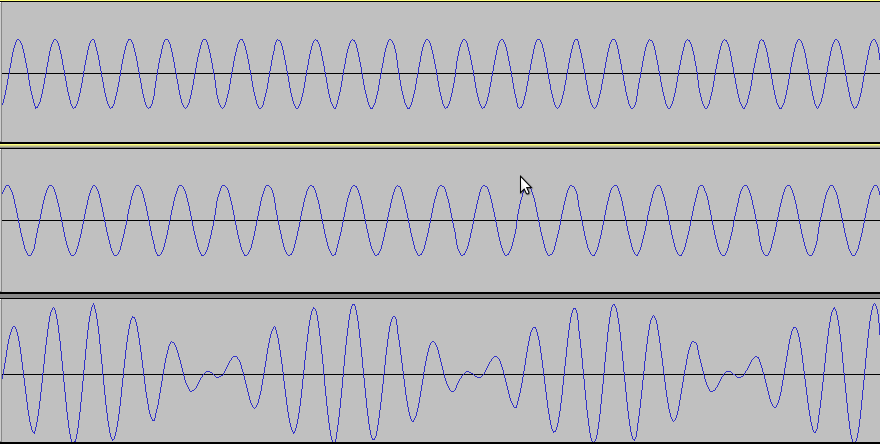

Below are two sounds, 2.333kHz on top and 2.000kHz in the middle, which,

when added together, make the sound on the bottom:

You can see in this image, that where the high and low parts of the

wave are together and line up, the waves get bigger. Where they

don't line up, they cancel each other out, and become smaller.

This audio file will play all

three tones, first 2.333kHz, then 2.000kHz, then the combination of

both. By combining the correct sets of frequencies, for the

correct duration, you can make any sound imaginable.

As we saw before, when we combine different frequencies, it changes

the height of the waves, this height (both positive and negative) is

called the amplitude, and represents how loud the sound is, also known

as its intensity. The

higher the waves go, the louder or more intense the sound you will

hear. This

scale is generally measured in decibels (dB). They range from

zero (0dB) being the quietest sound perceptible to the human ear (at

1kHz), to 194dB being the loudest sound that is possible to create in

the earth's atmosphere. Some examples in between: calm breathing

10dB, a normal

conversation 40-60dB, TV at a normal level 60dB, a busy roadway 85dB, a

jack hammer 100dB, a jet engine 130dB, and a rifle being shot

160db.

Warning on hearing damage:

Loud sounds, especially when heard

over periods of time, can permenantly damage part of the human

ear. If you spend long periods of time (8-10hrs/day for 6 months)

near a busy roadway (85dB) or if you spend even a few minutes near a

jet engine (130dB), you could do serious, permant damage your hearing.

To see an example of how the different intensities of sound show up on a graph, lets look at this

audio track,

from the trailer for the open source movie sintel, in audacity.

As it plays, you can see that the louder parts show higher peaks (and lower lows) on the

intensity scale. If you want to watch the video that goes with it

first, you can get that here.

Pulse Code Modulation - Wave Properties

When sound waves, or waves of change in air pressure, move through

the air, they always vary smoothly. There are never any

instantaneous jumps in pressure, just smooth changes in pressure that

can happen in incredibly short amounts of time. If we zoom in to

a small enough time, there will always be a nice and smooth curve, like

the last few above. Mathematically this is called being continuous

(in both time and frequency).

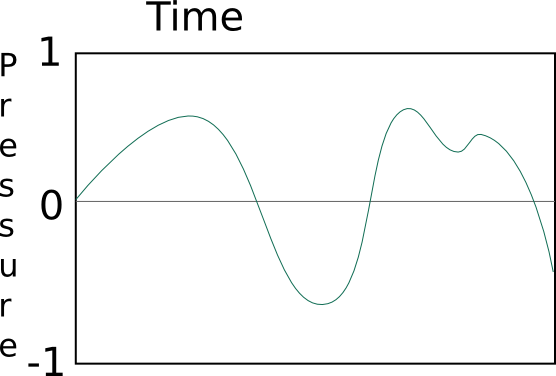

For example, this is a possible (even typical) graph of sound:

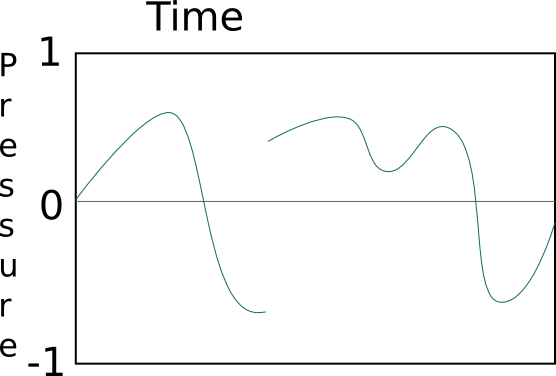

This is impossible, the pressure can not instantaneously jump from

one value to another:

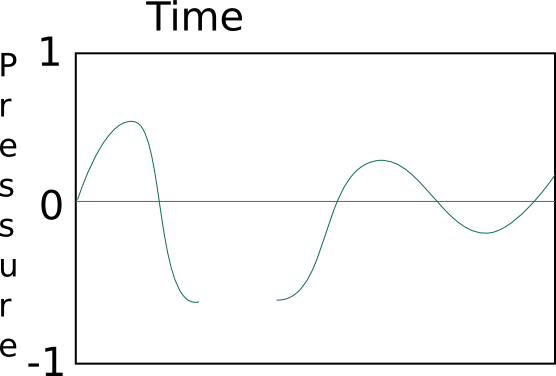

This is impossible, there is always some amount of pressure (even if

that amount is zero), it can never not be there:

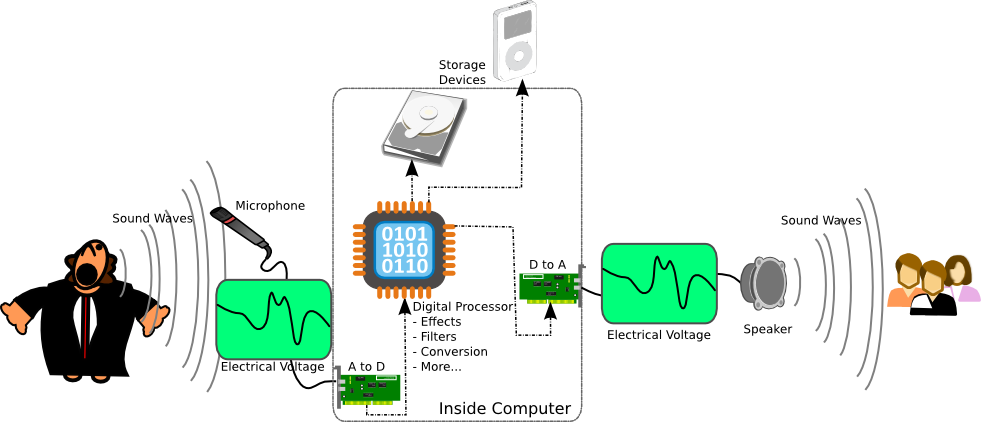

Analog to Digital Conversion

When we make an analog recording of a sound, say on a cassette tape

or vinyl record, we are recording the change in voltage output by the

microphone of the continuous changes in the pressure. However,

digital devices (Compact Disc (CD), computer, cell phone, etc.) are not

capable of storing this continuous data. For a digital device,

everything must be broken down into numbers (ones and zeros). So

the digital device can record a number of the amount of voltage put off

by the microphone. The catch is that it can't do it at every

instant, it has a limited number of times per second that it can make a

reading of the voltage and record its value as a number. The

general term for this is an analog to digital conversion (A to D, A-D,

ADC).

Luckily

modern electronics are very powerful, and can easily do one of these

analog to digital conversions many thousands of times every

second, each individual conversion being called a "sample". In

fact they are capable of recording so fast that the

human ear can't even tell that is was ever made into a digital

signal! The same thing happens when we play digital audio back

out. The digital device does a digital to analog conversion (D to

A, D-A, DAC) to

get the voltage numbers stored back to actual voltages of

electricity. Then the voltage travels to a speaker (or very small

speakers in headphones) which uses the change in voltage to run a

device that can make rapid changes in air pressure...and we hear

sound. These analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog conversions

are absolutely essential for audio, but can also be applied to lots of

other things as well. In fact anything that can be represented by

an electrical voltage can be converted and used as a digital

signal. These signals could be something as simple as setting the

level of light in a room, or as complicated as controlling a car's

engine when you push the gas pedal.

For more on these A-D and D-A conversions check out these articles:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Analog-to-digital_converter

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conversión_analógica-digital

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital-to-analog_converter

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conversor_digital-analógico

So once a digital recording device has done an analog to digital

conversion on a voltage signal, it needs to store that data digitally,

even if only for a moment while it is transfered to another device, in

general this is called Quantization (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantization_(signal_processing)

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuantificación_digital).

There are many ways to do this, but the most common one used for audio

is called Pulse-Code-Modulation.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pulse_code_modulation

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modulación_por_impulsos_codificados

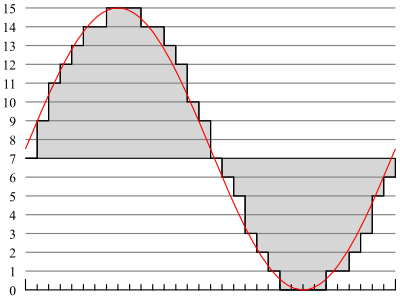

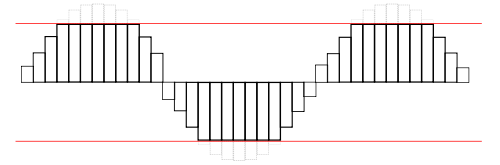

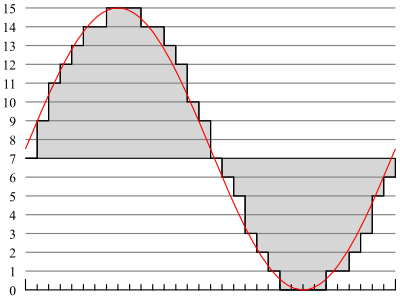

Pulse code modulation works by taking a sample at a certain rate (a set

of pulses every X microseconds) and storing the value as a "code" on a

scale.

Here you can see an example voltage curve in red. The line in

gray symbolizes the respective coding for the signal (on a scale from

0-15, 4-bit). Each hash mark along the bottom is one time

step.

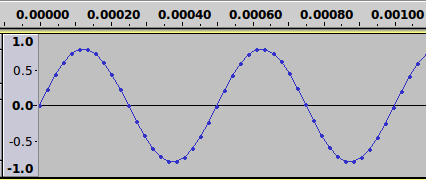

Here's another example, from the same 2kHz tone that we used

above. This time the graph is only about 1/1000th of a second

long (0.001 seconds). Each point that you see on the graph is where a

sample of the audio was taken.

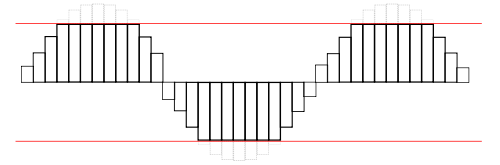

Bits Per Sample

One of the factors that determines how good a digital audio file sounds

to a human ear is the number of bits used to store the value of the

voltage that was converted to a digital signal. This is often referred to as the sample depth. When we worked

with images, we used 8-bits for each of our three color channels

(24-bit color). Here the most common format you will see is

16-bit which gives you 2^16 or 65,536 different possible values for

each A-D conversion. This is what is used in things like CDs and

iPods, however when audio professionals work in recording studios, they

often use 24-bit values (2^24 or 16,777,216 possible values) for richer

sounds. Using less bits will sometimes cause the audio to not

re-produce the sounds very well because anything that falls outside the

range of values will be clipped off.

Here's an example of clipping:

You can see that that the data that falls outside the values that can

be represented isn't correctly re-produced. This can then sound

like noise or muted sounds in your audio recording.

In addition to 16 and 24 bit storage, there is a method of storage called

"floating point". Floating point takes up 32-bits per sample, but

is used differently. 24-bits of the data are used to store a

value for the sample, the remaining 8 bits are used as an exponent.

This means that floating point values can represent extremely tiny

changes in value that are close to zero. It also means there is

effectively no upper boundary on the scale (in either the positive or

negative direction). An example of this can be found in the

image of the 2kHz tone above in the PCM section. Notice that on

the left, the scale goes from -1.0 to +1.0, instead of something like 0

to 65535. This is the typical way that floating point

values are written. In floating point, the signal is free to go

above 1.0 or below -1.0 without loss (there is no clipping in floating point). Because of this, floating point

values are often used during the recording and/or editing process.

Sample Frequency

The other major component that affects how a digital audio recording

sounds is the number of A to D samples that are taken every second,

also know as the frequency. This number is usually denoted in

Hertz (Hz) which simply means "cycles per second". The most

important aspect to choosing a sample frequency is the Nyquist

theorem. The Nyquist theorem states that to accurately re-produce

a sound, you need to have a

sample rate that is twice as high as the highest frequency you need to

re-produce. As was explained before, the human ear can typically

hear frequencies up to about 20,000Hz or 20kHz. This means that

the minimum frequency that we need to accurately re-produce sound is

40kHz. However there also needs to be some extra room to filter

out any stray (non-audible) frequencies, so the most common recording

frequencies are 44.1kHz for CD audio, and 48kHz for typical digital

audio. There are also some formats specially designed for

recording that go to 96kHz or beyond, and this is to allow for the

creation of even better filters for the non-audible frequencies.

Just because it takes at least 40kHz to accurately record everything

the ear can hear doesn't mean that lesser frequencies are not in

use. For example on telephones any time a land-line call

goes outside the neighborhood or any time on a cell phone the audio is

digitized at an 8kHz frequency. This sounds alright when you just need

to hear what the person on the other end is saying, but would sound

awful if you tried to listen to a musical performance digitized at

8kHz. In this day and age however, an audio engineer would only

look at using a sample frequency lower than 40kHz if there were serious

bandwidth or storage constraints. For this course we will use at

least 44.1kHz or 48kHz audio.

Endianness

Endianness is an artifact of the growth of computer technologies in

different organizations at the same time. This refers to the way

bytes are stored in a computers memory. The details of it aren't

important for digital media creation, just know that there are two

different formats: Big-Endian and Little-Endian. By themselves

they aren't compatible, but it is trivial for software programs to convert between them.

Channels

The channels used in digital audio are different from how channels were

used in images. In this case, each channel is a completely

separate recording, that just happens to be set to play back (and is often

recorded) at the same time. The channels are usually used to

represent the direction that the audio can come from.

Stereo audio has two channels, a left channel and a right

channel. This allows for sounds that seem like they are coming

from one direction or the other. CDs and FM radio use stereo

sound. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stereo_sound

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonido_estereofónico)

The more advanced format is called surround sound, which is generally

listed has having 5.1 channels. The five main channels are

front-left and front-right (these same as stereo, and are used when

there are only stereo outputs available), front-center, back-left, and

back-right. The .1 channel, is called the Low Frequency Effects

channel and is designed for use with sub-woofers that only produce

sounds from 3-120Hz. Because of this low frequency, it is

possible to use a much lower sample frequency with this channel.

However most computer hardware just treats this as its own complete

channel, hence computers that support surround sound are often said to

have six channel sound instead of just 5.1. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surround_sound

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surround)